Tales of Far Peru, Part 9

At Caxamarca visitors are shown the room which Atahualpa had to fill with gold and silver. There was to be a heap of golden ornaments and vessels, as high as the unfortunate Prince could reach, and as wide and long as his outstretched arms. The residue was to be silver. It is estimated that the room would hold treasure to the value of £100,000,000. Its dimensions are variously given as 22 ft. by 16 ft., and 27 ft. by 22 ft. Once part of an Inca palace, it is now used as a school.

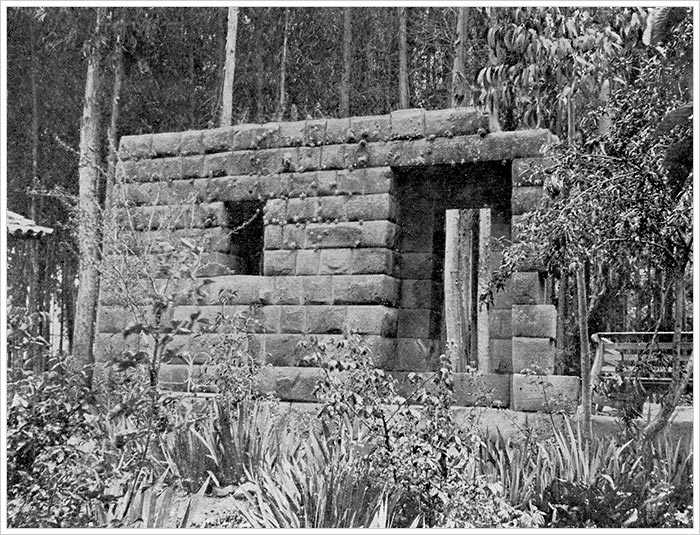

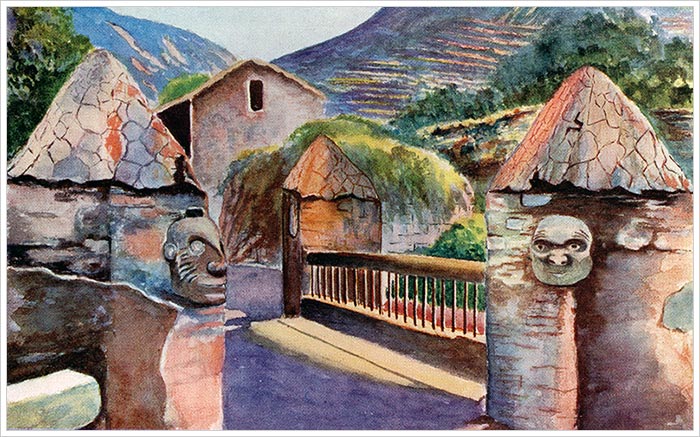

A water-colour sketch by the author of the old Inca castle near Caxamarca. Illustration from Adventures in Peru.

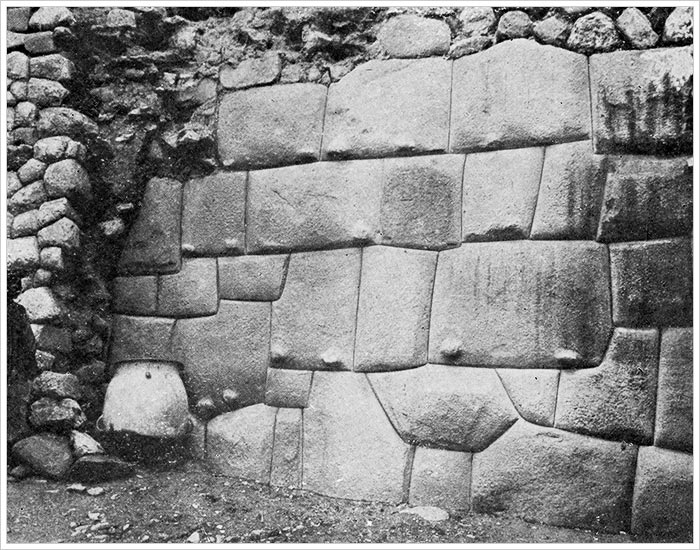

Not far from Caxamarca are the remains of a most tremendous building erected by the ancient Peruvians. It would hold, I should say, 4000 to 5000 persons, and was constructed of colossal stones. The vast ransom of Atahualpa represented not a tithe of the Inca hoards. There is no doubt that an immense amount of gold and silver (including the portion of redemption money that was being conveyed to Caxamarca when Atahualpa was condemned to die) was buried by the Indians directly they realized that the Spaniards had played them false.

One has but to read the writings of Benzoni and Raleigh to get some inkling of the limits the Spaniards went to. Raleigh relates how he saw Indian chiefs chained to stakes in the merciless sun, and their bodies basted with burning bacon, in order to make them disclose some of the hiding places. Benzoni tells of Indians stripped and laid on the ground tied to a piece of wood, and then lambasted till their bodies bled profusely. Boiling oil or pitch was next thrown over them, and a mixture of pepper and salt well rubbed in. This doesn’t afford pleasant reading. Happily it is not the record of cultured Spaniards, but only what one might expect of a band of ruffians burning with gold lust, and led by men of doubtful origin. Such uncongenial soil rarely produces much in the way of consideration for other folks’ feelings. I quote this by way of showing that, as far back as 1540, the belief in Inca treasure hoards was firmly held. I cannot help thinking the Italian referred to in my book on Bolivia obtained his gold ingots from one of these secret caches which he had discovered between Juliaca and Cuzco.

The author of The Antiquities and Monuments of Peru, and Markham in his history refer to a hoard concealed in the ancient fortress of Cuzco, by the Incas. According to them, a certain Donna Maria Esquivel was not satisfied with the style in which her husband maintained his household. She deemed it quite unworthy of his rank, and bitterly reproached him with having deceived her. “You call yourself Inca—a Lord—but you are only a poor Indian.”

Don Esquivel bore with her as long as he could, but eventually decided to open her eyes. (The Esquivels, I may say, lived on the outskirts of Cuzco and kept sheep and alpacas.) So he blindfolded her, turned her round thrice, and conducted her a little distance from her apartment to a vault, it is thought, under the ancient fortress. Then he removed the bandages from her eyes.

Donna Esquivel stared about her with amazement, for she found herself in a veritable chamber of Aladdin. Immense quantities of gold and silver ingots and ornaments littered the floor; and ranged round the room were statues of all the Inca kings, fashioned of pure gold. They were about the size of a boy of twelve. It is worthy of note that Donna Esquivel saw no golden image of the Sun—the treasure upon which the Incas set the greatest store.