Lake Titicaca, La Paz and Sorata, Part 3

At about five in the afternoon we put up for the night just outside a place called Machacamarca, not far from Lake Titicaca, paying the usual 2/- a night for the use of a room with a mud bed and fireplace, and finding food, firewood and other necessaries ourselves. Fowls, potatoes, barley and fresh eggs can always be bought at these places. At this altitude it takes seven minutes to boil an egg, at 15,000ft. it takes even nine to ten minutes. I arranged to rent the accommodation here for two days and bought a double supply of barley fodder for the mules, so that I should have a little time to walk along the shore of this magnificent lake and shoot a duck or two for a change.

Lake Titicaca is full of fish, mostly pejerey, about twelve to fourteen inches long, and very good to eat. Many of the Aymara Indians who live on the shores of the lake, besides growing barley, planting potatoes and looking after llamas, alpacas and sheep, do a good deal of fishing with their small nets from balsas made of reeds that are practically unsinkable. They take the fish twice a week into La Paz, Sorata, Machacamarca and other places, and sell it there. I bathed several times in the lake, but the water was too cold to remain in long. There are geese and duck to be shot on the banks near the shore, and on either side of the lake are stretches of flat lands covered with coarse grass and low bushes. Once a year there is a big fair of llamas, alpacas, sheep and little mules and horses held by the lake on the Peru-Bolivia frontier; another big yearly fair is held at a place called Juare, a few hours away on the Oruro-Antofogasta line. This fair starts on April 7th, and lasts a whole fortnight; all the Indians come from miles around to attend it, and mules are brought to it all the way from the Argentine. I always bought my mules there.

I shot some wild duck and some geese by the lake; the duck are good, but the geese are very coarse. I also shot a guanaco for my Indians; its meat is very rank, and to my mind most disagreeable, but the Indians seemed to enjoy it.

After spending a day on the shores of Lake Titicaca, I went on next day to Sorata, a little town lying in the valley of that name below the Ylliapo range, 8,000ft. high, and some ninety miles from La Paz. There I was put up by Mr. and Mrs. Gunther, who were most hospitable. Gunther is a large rubber buyer with plenty of capital, and the owner of a big rubber estate, also of the largest store in Sorata and the principal brewery in Arequipa. Both he and his wife did their utmost to persuade me not to continue my journey. The first night I was there, Mrs. Gunther told me that Mrs. Villavicencia, who lived opposite, had seen me get off my mule at their house, and had said to the Gunthers’ cook who happened to be over there at the time: “Do you see that big Englishman who has just arrived? He thinks he is going to get to Paroma to spy on the Indians of Challana and report to the Government at La Paz. Tell him they will never permit him to cross the river, and that if he persists they will attack him and kill him.”

When I heard this, I asked Gunther to introduce me to the good lady, which he did next day; he just presented me and then left us to talk together, and I conversed with her for two hours. I told her my object in undertaking this journey, explained to her the proposal I was going to make to the Indians, and begged her to send one of her men to her brother Villarde, asking him to get the necessary permission for me from the Cacique to cross their border and visit him at Paroma. She told me to come back and see her the next afternoon, and she would let me know then what she could do. That night at dinner Mrs. Gunther said to me: “I don’t know what you have been doing, but you seem to have made a very good impression on Villarde’s sister; she says you talked with her and treated her quite differently from all the others who have been to see her about visiting Villarde, and the old chief at Paroma, and she has actually decided to send a messenger for you to her brother.”

Next day, as arranged, I called on Mrs. Villavicencia, who received me in a most friendly way. She told me she was sending a letter on my behalf to her brother, Villarde, by the hand of an Indian whose home was near Paroma. She said her brother had been made a chief by the Cacique, and was also at that time interpreter for the Indians; her husband was there too, working under Villarde. She advised me to let the Indian have a fortnight’s start in case her brother was away when he arrived.

Gunther insisted upon my spending the fortnight with him and his pretty wife, which was very nice of him. While I was at Sorata I used to go down the valley every day and admire the beautiful big cacti that grow everywhere about there, in all colours from pure white to dark purple and bright red; also the brilliant single and double fuchsias, which are much larger than any to be seen at home. This valley is full, too, of rubber vine, a plant that yields an inferior kind of milk.

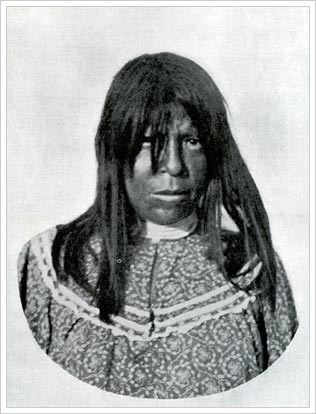

Most of the Indians living hereabouts are Aymara, and own sheep and llamas. There are some large estancias (ranches) owned by rich Bolivians who spend most of their time in La Paz, leaving their farms in charge of a manager, generally a half-caste, with some Indian shepherds under him. Sheep do well, and give 6lbs. to 10lbs. of wool a head, and 50lbs. to 60lbs. of meat, good mutton and cheap, costing only 4/- to 5/- the head when the wool is off. Alpacas also do well in this district; they prefer the flat ground nearer the lake, while the sheep roam the hills and higher slopes. The sheep are tended by Indian women, who sit near them in sunny places or walk among them with wooden spindles yarning skeins of wool which they pluck from time to time off the sheep’s back. Many of these women make excellent socks and stockings out of this worsted spurn, which they have a special way of treating. I have bought several pairs and always found them far more durable and better in every way than any I have paid good prices for in England; indeed, I am never without them if I can help it. The Indian women sell them in sheep and llama wool at 2/- a pair; they also make them of vicuña wool, but these are more expensive, and run to 4/- or 5/- the pair.