More endpapers, this time from the first edition of Adventures in Bolivia.

Category Archives: Ephemera

A Real Bohemian

Like its predecessor, Adventures in Peru was reviewed in one or two journals of note. Here’s a contemporary review from the literary supplement of The Spectator, written by Prodgers’ friend R. Cunninghame Graham (who, as you may remember, also wrote the foreword to Adventures in Bolivia).

Adventures in Peru

Those who have read his Adventures in Bolivia require no introduction to the man. The irony of fate has cut him off with half his work undone. No one who knew him could have connected him with death, for he seemed built to set at naught the ravages of time. If he did not die, as such a man would surely have desired, in his boots, at least he left the world almost without a warning to us that he had got Blue Peter hoisted at the fore. Within three days of his death he was riding his gigantic chestnut horse (he himself weighed three and twenty stone) and having dismounted he was gone almost without farewell. He left the world the poorer by the disappearance of a type, for he was certainly an arch-type of an adventurer.

Of the same breed as Hawkins, Frobisher and Drake, he had, as Diaz del Castillo (another born adventurer), a curious felicity with his pen, not, of course, the curiosa felicitas of which Petronius speaks, but a felicity that comes from great sincerity and absence of all artifice. There are phrases in his Adventures in Bolivia that remain bitten into the mind, not bitten in with acid; no acid entered into his composition, for certainly “he was a goode Felawe” like Chaucer’s shipman; but still indelible at least to those who like the Black Douglas ever love better to hear the lark singing than the mouse squeaking.

His second book, Adventures in Peru, moves on the same lines as the first. There is still the feel of open air about it, still the same spirit of adventure and the joy of life. One feels that the writer was a man speaking to men, and not a phrase maker, with one eye on the public all the time. Such kind of books when written by a Diaz del Castillo or a Herman Melville are immortal; nothing can kill them as long as grass grows green and water runs. Both these two writers were, of course, men of genius, and genius has a lien on immortality. Prodgers falls into a different category. His “genius” was for life, not literature. All sorts and conditions of men knew him, from the President of Peru, Señor Leguia, himself a man who has had countless adventures and been in danger of his life a hundred times, to the rough sailors, herdsmen, dealers and storekeepers of whom Prodgers has left us in his two books almost as great a gallery as did George Borrow in his amazing Bible in Spain, that marvellous tale of sowing seed, so to speak, on asphalt pavement.

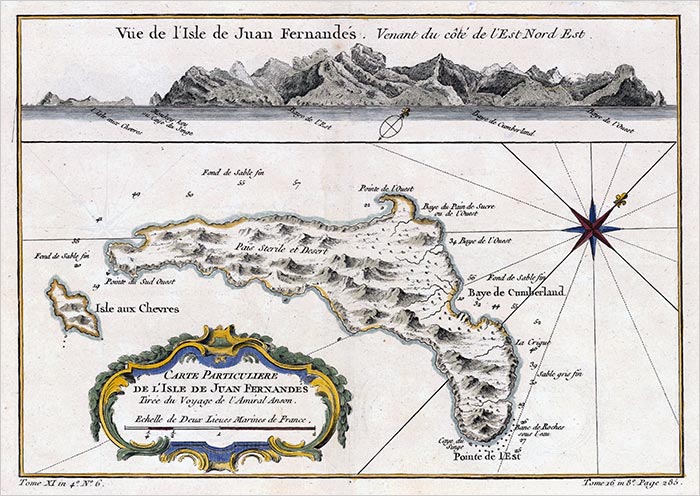

The second book is lacking here and there in those small touches that only the author’s hand, although a hand more used to rifle and to bridle than the pen, can give. Still it contains some curious chapters, and notably his descriptions, curiously minute, of Juan Fernandez, the island where Selkirk passed the four years that were to be immortalized in Crusoe by Defoe. Without a word of introduction Prodgers plunges into his yarn. “At the time when poor Kemmis went broke and there was nothing doing Las Rosas way, it behoved me to look round for another job.” This sentence proves to demonstration that “le style, c’est l’homme.”

To read it is to hear the author talking as he talked in life. He goes on to say: “I didn’t believe in loafing about Santiago on the chance of something turning up.” I maun premise, as Scottish theological disputants used to say, that Las Rosas is an estancia in the province of Santa Fé, in Argentina, and Santiago is a thousand miles away from it, “mile more or less,” as runs the Spanish phrase, for I believe the actual distance is not quite the thousand miles. “So I broke altogether new grounds. Hearing that Kuhn and Co. had bought the wreck of the ‘Telegraph,’ stranded at the Isle of Juan Fernandez, I got in touch with them and obtained the job of superintending her breaking up.” All this is Demosthenic in its directness. We are left without the smallest indication as to who Kuhn and Co. were. We do not want to know. All we know is that Prodgers, who had been for several years a racehorse trainer in Buenos Aires and afterwards manager of the horse ranch at Las Rosas, has now turned seafarer. Captain Brunn’s powerful tug, the ‘Pachuco,’ was commissioned for the purpose—that is, to draw the stranded ‘Telegraph’ across the hundred and sixty five miles of sea that separate the Isle of Juan Fernandez from Valparaiso, or as a friend of Prodgers used to call it “Val”!

“In addition to her own complement [number not stated in the text] she carried an auxiliary crew of eight men under Captain Brunn to man the ‘Telegraph.'” Prodgers, nothing daunted, at once assumed command and put to sea, possibly thinking that a ship is steered as easily as is a horse.

That was the way the Elizabethans, his spiritual ancestors, embarked to discover continents. They did not count the costs; no men did that. To such men adventures come as easily as coughs and colds to ordinary folk.

His description of the island reads like a page of Captain Cook. He does not launch into fine writing, describing mists with their pale opaline tints shading off into deepest orange, that again faded to a palest yellow, reminding one of the reflection on the petals of a flower cast by the iridescent wings of dragon-flies. Still, what he says accurately describes the scenery and brings it up before the reader’s eye far better than when the writer like a vulgar orator appears to listen to his own words.

What more does anybody want, unless the writer happened to be a Conrad or a Hudson, to whom nature had given so high a sense of colour and such a felicity of words ? His love of flowers is one of his chief characteristics. No matter where he is, he never fails to notice the flowers. In Juan Fernandez he remembers that the island contains “twenty five species of ferns growing in this lovely island,” and notes the Helecho fernandisciana, and the Helechos brunato and disksonia. In a journey through the desert valleys of Nasca and Cañetê he saw “a lovely bush of wild jasmine. I have never seen a bigger or finer specimen; entwined with it was a gorgeous blue convolvulus creeper. In my humble opinion nature had provided this as a protection for the beautiful bush.” The way he writes shows him to have had, in regard to flowers, something of the attitude that Hudson had to birds. Throughout his pages these references to flowers are frequent and sometimes come in almost strangely after some yarn of hunting, shooting or deals upon the stock exchange. Something there is of Borrow in his writings, especially his love for horses and in the way he loves to dwell upon good cheer. “I loaded up the cargo mules,” he says in one place, “with provisions, not forgetting to include some old Madeira, half a case of whiskey, six bottles of old port and several bottles of Liebig’s extract”—not a cargo for a trip into the interior, even for a man who weighed some twenty stone.

There is, too, something of Smollett and Fielding in his literary make-up. Not that he is ever coarse, in matters sexual, but in his intense enjoyment and delight in physical existence, a state of mind (or body) that seems nowadays to have gone quite out of fashion, or at least to be a thing to be kept in the dark. In fact, he is a real Bohemian, and a Bohemian by nature, not a person playing at Bohemia with a waiting taxi-cab to take him home when he gets bored.

Everything interests him in life, a gallop on a frosty morning on the Andean uplands, a Guanag hunt, a storm at sea, flowers, as I said before, fine horses, adventure for its own sake, and pretty girls, as when he says, speaking of some Indian women, who thought that he was mad because he took a cold bath every morning : “I could not help feeling flattered by the interest they took in me, for if the group included a sprinkling of withered old women, the majority were robust and well set up, and some of the girls very good looking.”

Nor did this joy of life exclude an interest in scientific matters, for he recalls with pride a correspondence that he had with W. H. Hudson about the Condor Real (the king of the Condors) reputed to be white. Hudson at first doubted the fact and thought the bird must have grown white with age. However, certain facts that Prodgers laid before him changed his opinion, and Prodgers says with pride, “Not long before his death, however, he was good enough to write and say … that I was right in concluding the Condor Real is a distinct species and a pure white bird.” A sportsman to the core, claiming for himself no special conscience about the matter—after the style of some who murder animals for fun or “to get specimens,” and then stand weeping tears of hogswash over their “fast glazing eyes,” he still remained humane as occasional incidents testify. Having raised his rifle to shoot at some Vicuñas, “they looked so beautiful that I felt I could not pull trigger on them.”

One thing one hopes the Recording Angel took due notice of, and blotted out some of the actions that Prodgers, like most other men, must have wished blotted out of his account. In the sympathetic memoir that his friend, Charles J. Maberly, writes of him, he refers to Prodgers’ part in helping to bring the Putumayo atrocities before the world. Prodgers himself just notices his part, in passing, saying: “I have never regretted participating in bringing them (the atrocities) to the notice of the world at large.” Further on he speaks of what went on in Putumayo as “devilish” and “cruel.”

An interesting book, discursive and written in a style that one is apt to think perished with Captain Cook and Mungo Park, but that crops up now and again and shows that the old Elizabethan never dies amongst the English race. To make the analogy complete, here and there crop up views of great simplicity, as often happens, as it seems to me, with men who spend their lives with nature cheek by jowl.

“I am much interested” (he says) “in missionary enterprise” (who would have thought it?) “and am filled with admiration of the wonderful work some of the missionaries have accomplished in various parts of the world, but I cannot shut my eyes to the fact that in South America, at least, the Gospel message seems to have had a disastrous effect on the morals of the Indians. This may, of course, be attributable to the fact that the trader with the rum-bottle follows hotfoot after the Gospel Messenger. Until the tenets of Christianity were preached to them, immorality” (he means sexual immorality) “was practically unknown among the Indians … as a Christian I cannot but feel humiliated when I think of the change that comes over some of the tribes after they have heard the Word and received it gladly.”

Neither Corporal Trim nor Uncle Toby could have bettered this delightful paragraph.

—R. B. Cunninghame Graham.

The Spectator (Literary Supplement), 4 October 1924, pp. 461-462.

Map of Juan Fernandéz

A map by Jacques Nicolas Bellin of Juan Fernandéz Island from 1753—a fair bit before Prodgers’ time, but there aren’t any from around 1900 that I could find online.

Farewell to Bolivia

And so we say goodbye to Bolivia and to Adventures in Bolivia, Cecil Prodgers’ first book of travel memoirs. The book was enough of a success that he quickly wrote and published a sequel, Adventures in Peru, which will appear here soon. A third book of horse-racing memoirs from Chile was sadly never published.

Searching online for traces of contemporary reviews of Adventures in Bolivia turned up only part of a five-book review of travel writing about South America in the New York Times, reviewer unknown. I’ve reconstituted it from the abstract and from an OCR version of the original page, which involved some guesswork for a few garbled words. The $50,000 figure is based on a conversion rate to pounds sterling of approximately five to one in the early twentieth century.

Spanish America Through Foreign Eyes

Of the five books listed, that of C.H. Prodgers hits the highest note in the scale of adventure. We can imagine this man, who weighed 265 pounds before he undertook a venturesome and dangerous journey, making his preparation to venture in where white men had always feared to go. As the story tells, he was very comfortably situated as the trainer of a large stable of horses when he was offered $50,000 to enter the Challana territory for the purpose of establishing a spirit of good-will between an exploitation company which had concessions there and the natives. In a most matter-of-fact manner he tells how he undertook the hazardous journey, not so much because of the honorarium involved, but because he would get an opportunity to see Lake Titicaca, the highest navigable lake in the world, and visit the peak of Sorata, the ultima thule of much adventurous endeavor.

Recognizing that his avoirdupois might prove a serious handicap in his quest, Prodgers went about its reduction in a most business-like manner. In a few weeks he had worked himself down to the comparative lightness of 235 pounds and started merrily on his way. His mount was one of the small but sure-footed mules which are used for transportation in this territory. The appearance of this modern Sancho Panza with his heavy torso draped over a mule’s back must have been very interesting, and genuinely entertaining to all beholders; his pack was borne by a horse which in the days of his horse training had served him to some purpose. Everything that Prodgers set out to do he did without much exertion on his part, according to his own narrative. Obstacles appear to have tumbled down before the very assurance of his goodly presence. There is a certain modesty about the whole story that appeals to men who are familiar with the country through which he passed and the suspicion directed by the natives against every white man.

Not satisfied with having performed his duty to the rubber exploiting company which sent him into Challana and with having seen the things which formed part of the urge which sent him forth on his adventuring, Prodgers undertook a search for missing treasure, the fabled treasure of the Incas. In this effort he made three attempts, but without success. Were the story not so real throughout, it would find a welcome place in the fiction of adventure. No one could read it without feeling its fascination. It might be questioned whether the writer has added much to the sum of knowledge about Bolivia. The answer to this is that he has done the few things he attempted along this line in a most readable manner. There is a lengthy introduction to the volume by R. B. Cunninghame Graham, whose adventures as a big game hunter in all parts of the earth are well known in this country. He will be best remembered as a friend of Theodore Roosevelt and one of the members of his party during his African trip. The introduction is well worth the reading because Graham is doubly gifted as a writer and an adventurer. As he intimates, Prodgers may have been “too stout for active virtue,” but he shows how one writer “got there,” and that, after all, is the most important thing.

The New York Times, 24 December 1922, p. 45.

Our Man at the Baths

The thought of our man Prodgers at the Jura baths brings to mind another stout moustachioed figure who was inordinately fond of them…

Colonel Blimp by the incomparable David Low.

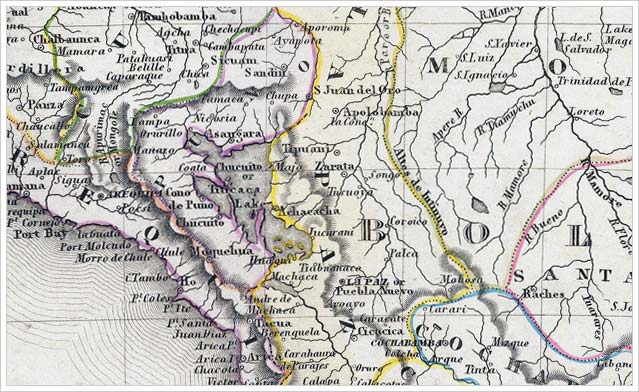

Map of Prodgers’ Vicinity

Detail of an 1847 map of Peru and Bolivia showing the area of Prodgers’ Challana expedition.