Arequipa and the Jura Baths, Part 2

There are two ways of staying at Jura. One is to put up at the hotel built by Morosini, an Italian, who was given ground and other facilities rent free by the Municipality of Arequipa for twenty-five years, provided he built an hotel with accommodation for ten or twelve guests, and was allowed to charge 6/- a day. The other is to rent one or more of the little stone houses owned by the Municipality for £3 a month each; these consist of two rooms with two chairs and a table in each, a kitchen and veranda, two mud-built beds, a brick oven, and the usual mudrange to hold four or five pots.

Fresh mutton is brought by the Puno train, and fresh meat by the Arequipa train twice a week. The Indians round about always have fowls and eggs to sell. There is some partridge and duck shooting to be got in the neighbourhood, and occasionally some guanacos; but guanaco meat is not worth bothering about when you can get fine mountain sheep for 6/- and 8/- each. Some of the most beautiful cacti grow hereabouts, and there are flowers of all colours, red, or slate blue, yellow, white, purple or pink, all as large as saucers, with several on each stem. There is a good sized stream or river which runs for twenty miles underground near here, and then appears again. Several families of Indians live in this district with their llamas, and fine-looking long-haired donkeys, which have the peculiarity of four holes in their noses, instead of two; they have the ordinary nostrils and then another pair, about half an inch round, two inches higher up.

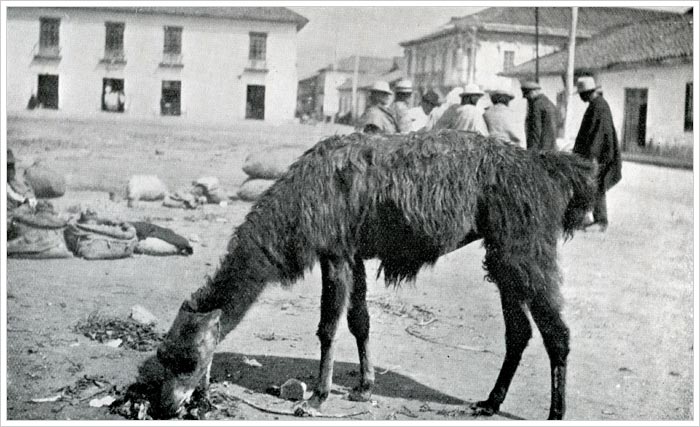

A llama. Illustration from Adventures in Bolivia.

Morosini told me that some few years ago when he was keeping a rest house at Juliaca, where the line branches off to Cusco, the capital of the Incas, where they built the Temple of the Sun, he knew an Italian who had discovered where some of the Inca treasure was hidden. Apparently he had made his home near that place for two years, and used to disappear every now and then with two mules, provisions and gear, staying away for five or six days, and coming back with bars of gold weighing two to five kilos each, which he took to the bank at Arequipa.

Morosini tried hard to discover the hiding-place of this treasure, and once he followed the fellow; but he never succeeded in finding the place. All he could gather was that where this gold came from there was a lot more, and that the Italian had been shown the place by an old Indian whom he had accidentally found coming away from it one day. The Indian bound him to secrecy, and made him promise that he would only take away with him just what he could carry up the steep mountain path. There was nobody living anywhere near the place, and it was extremely well concealed; the Italian made several trips to this place during the two years Morosini knew him, and then went back to live in his Italian home. He had come out to Peru to prospect for a gold concession, and had struck this find by pure luck; he was practically a teetotaller, so there was no chance of his disclosing the secret in his cups.

While I am on the subject of the Jura baths I ought to say something about a few more of the old Inca baths. A couple of years before I went to Jura I visited out of curiosity the Lago Huacachina (which means the lake for incurables). To get you there take the steamer to Pisco, two days south of Callao, and then the Pisco-Ica train across the 40 miles of desert which separates the two places. On the way at a little place where the engine takes in water I saw the most magnificent bunch of heliotrope I ever saw in my life anywhere; a wonderful mass of flower it looked in the middle of this sandy desert. On arriving at Ica you hire a horse or a mule and ride 16 miles, then up a 3,000ft. sandhill at the finish, and then down 1,000ft; and there lies the Lago Huacachina. There is a rest-house there with blocks of two rooms each, mud bed, mud fireplace, and oven, table and two chairs in each, and you pay a rent of 2/- a day to the caretaker and find your own food. There is tropical vegetation all round the lake, which is about 300 yards long and half as wide, with a flat-bottomed boat on it which anyone can use; I took it one day in order to find the depth, which was exactly 17ft. on the average, from about 20 or 25 yards off the shore; the deepest part was in the middle.

I met here one John Robson, a rich brewer, who had come because he had got a stroke all down one side. He told me he had been there just three months and could walk about again as well as ever but the trouble in his arm was not right yet. I suggested he should go in like a dog on all fours and give his arm the same chance as his leg. He said he had never thought of that, and would certainly try it. Two years later I met a man who knew him and who told me that John Robson was quite cured and came back well as ever after eight months on the lake.

Another man, Piccione, an Italian, had had a bad fall from his horse while jumping a fence in Italy, which smashed his head and gave him concussion. He recovered, but ever since then used to suffer from severe headaches, and could find no remedy till he went to this lake, stayed there six months and was quite cured. I met Mrs. Piccione and her daughters at Pisco, and she told me that it was now nearly three years since they left the lake and that he had had no trouble with his head since then.

The baths are free to every one and there is no special course of treatment; you simply bathe in the lake and the waters do the rest. It is advisable, however, not to stay in for more than twenty minutes at a time. The caretaker told me that more than one death had occurred through patients staying in too long at a time. The water contains, among other things, iron potash and sulphur.

In Jura the waters contain magnesia as well as the potash and sulphur, and the Municipality have put up a notice forbidding people to remain more than fifteen or twenty minutes in the No. 4 bath. This one is the hottest and most dangerous, and there is a policeman always on duty there.

Another of the old Inca Baths is Cauquenes near Santiago in Chili. This is a pretty place but the waters are not very strong; it is more of a health and rest resort. Then there are the Chillan baths; to get there you take the train from Santiago to Chillan, an all day and all night journey; then you can drive the remaining ninety miles by coach with frequent change of horses or mules. These baths are owned by the Municipality of Chillan, and are only open for the summer months, from November till March, as they are under snow for the rest of the year. There are three hot vapour baths there called El Toro, Novillo, and Vaca; the first, meaning “bull,” is the hottest, the second means “steer,” and the third “cow.” There is a Government doctor kept at the establishment to see that nobody stays more than eight minutes in the Toro, which is like the hottest room in a Turkish bath, only much hotter. There is a good hotel there open from November till March.

Then there is also the Puente Inca on the way across the Andine Railway from Mendoza to Los Andes and several others. But the best of these baths in my opinion are Lago Huacachina and Jura.

While I was at Jura I met a Norwegian who had just returned a few weeks before from the Tipuani River, on the way to Challana. He begged me not to go and told me I would be killed if I tried to cross the river, but, anyhow, he said I would never get there as I would have to walk on foot over the 17,000ft. Ylliapo range of mountains, and that I would never be able to do. When I asked him why not he said I was too big (I was then still 265lbs.), and told me he himself had been offered £500 to go and make a report on the gold washing on the Tipuani and got so knocked up that it took him two years to recover sufficiently from the journey to walk back; he was staying there for three months to recover his health.

After staying at Jura for three weeks or a month, I had reduced my weight from 265lbs. to 235lbs.; so I sold my horse back to the original owner for £16, and left for Puno.