From Tipuani to Paroma, Part 11

In the morning I had a pleasant bathe in a lovely cool clear pool in the river just below Villarde’s house, and after a good breakfast we went off at 8.30 to the Court House, escorted by some of the head men.

The Court House was a very long shed, with logs of whole trees placed all round for seats, and a raised platform of logs at one end, where the old Cacique Mamani sat. Villarde sat on one side of him, and another man, named Portugol, on the other; beside these were Villarde’s other lieutenants, the two Fernandez, two more whose names I have forgotten, and an old man called Jones, who told me he had been in Challana for forty-two years and had quite forgotten his own language; he never said why he had come to this out-of-the-way place, nor why he had remained so long, and of course I never asked him.

There were three hundred Indians congregated in the building; thirty armed head men kept walking round between the logs and in the centre of the house to keep order, and there were others keeping order outside.

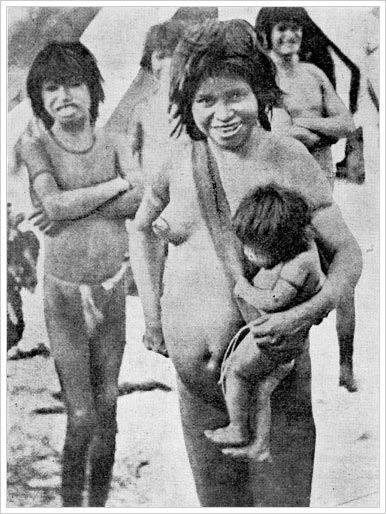

Natives in the interior of Bolivia. Illustration from Adventures in Bolivia.

The sitting lasted until five in the afternoon, when they all dispersed until eight the next morning. Many questions were put and answered, and there was a good deal of talking in their language; Villarde interpreting to me in Spanish, and I answering him in the same language.

When I got back, I had another bathe in the deep pool before dinner. Next day the conversation was renewed till finally Portugol said to Villarde in Spanish, “What can we do, Don Lorenzo? We shan’t be able to contain them much longer.” Villarde then asked me to get up and speak to them myself. I told him I could only speak Spanish, but he said that would do very well, as he was there to translate what I said, and if he did not translate correctly there were forty Indians there who understood Spanish and would correct him. So I got up and talked to them for two hours, telling them I was their friend and had come there to do what I could for them with the Government for their own benefit. I asked them what good it would do them to kill me, and told them that although I had heard that they intended to keep me there as a prisoner I came on alone, because wherever I had been I had heard the Challana Indians always spoken of as Christians, and I was quite sure they would do me no harm. I said I had come quite unarmed to see their country and visit their Chief, having left my revolver, rifle and cartridges with Cortez at Anhuaqui, and assured them that there was no truth whatever in the story of my being a spy; the Government of La Paz never sent me or anybody else there for that purpose. The Cacique then got up and embraced me, saying I was to consider myself their friend, and could come and go when I pleased. He told me I was a brave man, because I had come there alone, in spite of what I had heard about them; that they respected me and welcomed me, and were ready to listen to the Company’s proposals, and to tell them, through me, what they thought of them.

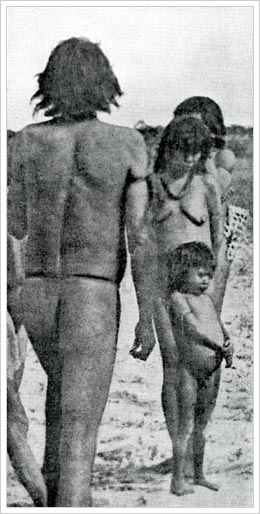

Some native types seen in the interior of Bolivia. Illustration from Adventures in Bolivia.

I then explained the Challana Company and Government’s suggestions, which were that five hundred of the inhabitants should pick rubber for the new Company at the rate of 100 bolivians a quintal placed on the Tipuani side of the River Challana, or on the other side of the River Tongo, the payment to be made half in cash and half in goods. Further, I was to see General Pardo, the President of Bolivia, with a view to his granting the settlers in Challana their holdings free. The Cacique told me through Villarde this proposal was approved by him and the settlers in Challana, and he said that, out of the nine hundred inhabitants of his country, certainly five hundred at least would pick rubber.

Villarde told me later on that at one time he and the other white men feared that the situation would become really serious. “I thought,” he said, “we might be able to save your life, but we were afraid they would not let you leave the country again. However, the yarn you told them about your hearing of the Challanas in London and New York as brave Christians and not savages, and all that, saved you; by keeping your head, you saved it, and if it had not been for the way you spoke and the impression you made they would undoubtedly have kept you their prisoner.”

Once they had decided in my favour, the Indians treated me very well, and old Mamani presented me with a valuable silver necklace, the buckle of which showed it to be the work of the Incas.

I subsequently took it home to give to my mother with a few other things.