From Tipuani to Paroma, Part 12

Challana is a beautiful country, full of dense forests, wide savannahs (grass land) covered with long nutritious grass, undulating hills and valleys, and many rivers and streams. Besides the yams, ochres, ucas and other vegetables and fruit indigenous to the tropics, rice is cultivated, as well as more coffee, sugar and coca than is consumed in the country. The rice grown here is of the very best quality, and the coffee as good as yungas. Coca yields five per cent of cocaine, and cinchona bark five per cent of quinine. Maize is grown by every one. The only things required from the outside world are hardware, drills, cottons and prints, salt, soap and flour. The Indians make their own rum, grow their own cattle for beef, and keep pigs, fowls and turkeys; several have cows and mules. Before I left, I got orders from them through Villarde and other head men to bring them back goods to the value of £5,000, to be paid for in rubber, at 100 bols the quintal, and, besides transporting the rubber to the Challana River free, they even offered to carry it on from there to Lake Titicaca or La Paz, for 17 bols a quintal. This same rubber easily fetched in La Paz 228 bols per quintal. Many of them told me that when I came back they would show me good places for gold washing, and would work for the Company if I was manager.

Not only is this country surprisingly rich and beautiful, but there is also plenty of shooting and fishing. The Indians are friendly, and travelling is not bad after reaching the top of the first steep hill. The climate on the hill-top at Paroma is not a bad one for the tropics, and Europeans with energy and capital could make good money and do well there; but it is not at all suitable for the manual labourer, as the climate will prevent him from doing as much work in a day as an ordinary Indian can; besides which, plenty of Indians will work for 2/- a day and find themselves, or 1/- and be found. This applies really to all the tropical parts of South America. Many a time I have been asked by English, French, German and other Europeans what sort of pay is obtained in these rubber and gold districts, and I have always advised them not to expect more pay than the Indian worker, unless they are mechanics or practised electrical drillers, in which case they would have no difficulty in getting jobs and pay accordingly. The reason one meets so many English and other Europeans down on their luck in the tropics of South America, walking from one district to another or one republic to another with half their clothes worn out, and little or no money in their pockets, is that they will not realize that the sugar planter, coffee grower, farmer or owner of rubber or mining concessions will not pay more than Indian labour will cost them.

The day I left Paroma the Cacique Mamani came to Villarde’s to say good-bye, and told off Cortez and three men all armed with rifles to take me back to Challana, calling them up in front of Villarde’s house, and making them the following speech: “Thomas Cortez, I have decided to send you with the three armed men to escort our friend to the Tipuani side of the River Challana. You are to be careful to look after his welfare in every way: it matters not whether he chooses to take one week, one month or one year on his way to the Challana, you will be held responsible by me if he is hurt in any way.”

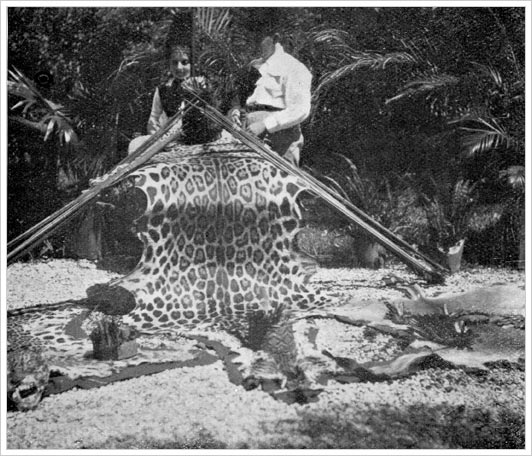

Before I left Paroma, Villarde gave me a document, stating that I had visited the Indians at their headquarters, and conferred with them: he signed it himself and it was witnessed by all the other Chiefs and head men. Near the River Challana I helped to get one fine specimen of a man-eating jaguar or tiger while he was chasing wild pig; the skin measured 8ft. 11ins. in the green, which I afterwards gave to the friend I trained horses for, M. M. Penny. The Indians gave me two other skins, and some snake skins, feathered caps, bows and arrows from the Beni and San Antonio.

Jaguar and puma skins, bows and arrows and wooden spears brought back by me from Bolivia. Illustration from Adventures in Bolivia.

Next day I started back with my escort, taking with me a collection of butterflies, and a little black monkey I had got at Paroma. We did the sixty miles to Cortez’s place at Anhuaqui in two days. I gave them some quinine and a few other things, and we parted the best of friends. Before leaving, Cortez said he had been asked to tell me that when I returned the settlers on the river were going to present me with a big nine pole balsa, so that I could go back down the Challana to the big river, meaning, I expect, the Gy Parana. By the order of the Cacique, Cortez told off an Indian boy to go with me as far as Tipuani, and look to the mule and fag for me. Next day they put me across the Challana, and I stayed for the night with Bartelot, who was down with another bout of fever.

On the third day we got to Tipuani; on the way back I saw some more of the pretty yellow-headed birds, with green body, purple wings and scarlet breasts. I was sorry I had not my gun, or a small bore pea rifle with me, so that I could get a couple of specimens, for this was the only place in which they were to be found. Before the boy returned next day, I made him a present of some tins of sardines and packets of matches, and a cutlass to take back with him for himself and friends; money would not have been much use to him, and I did not want to risk his running amok, as Villarde had told me that drinking to excess was not permitted in Challana. In fact, while I was there I never saw a drunken man, nor yet an immoral woman.

Perez still had the fever, Mac was just getting over his attack, and my man Miguel was still so weak that I had to wait for another two weeks before he could travel. So I amused myself by bathing in the Tipuani, shooting a few birds and catching a lot of butterflies. One day when Mac and I were shooting birds for the pot, we saw a big flock of dark brown pigeons, which Mac called “the lost tribe.” Sometimes Mac and I panned out a little gold, and we got nearly four ounces from pay dirt dug out by Rayo and Charlie in three days’ digging. A few days after I got back to Tipuani, two half-castes and a boy came to me, and suggested that as they were going to Sorata or La Paz with rubber for the house of Perez and Co. it would be safer if they could travel with me, as I was armed and had two men with me; by travelling all together we were less likely to be marauded by cut-throats or brigands on the way. I agreed, but said that I could not start for another week, owing to Miguel’s fever. Rather than travel alone, they waited for me, but unfortunately, just as Miguel began to get fit, Richardo, who was with the three small cargo mules, said he had fever, which meant a few more days’ delay. The half-castes said they could not wait any longer, for fear Perez might find fault, so they started off with Perez’ old grey mare and five small mules and ponies, each carrying a quintal of rubber. Three days after they left, I said good-bye to Mac and began the return journey to La Paz. As the rainy season was now over, walking through the forest and admiring the beautiful tropical plants and ferns was very pleasant. On the second day after leaving Gritado, the path on the edge of the forest gave way, and one of my small cargo mules fell and rolled down through tree-ferns and trees, right into a stream of water below. Unluckily for me, he was the mule carrying all my photographic plates, sixty fine views, as well as ten biscuit tins full of butterflies. The mule was not hurt, but many of the butterflies were spoilt, and when I took the plates to be developed at Lima later on only three came out a success, the rest were hopelessly blurred. This is why there are so few photographs in this book.

Prodgers’ reference to the old boarding school tradition of fagging (performing menial chores for a more senior boy) certainly dates this passage.