Indian Poisons and Medicinal Plants, Part 4

During my stay on the banks of the Appurimac near the old Inca bridge, I enjoyed several talks with Father Francisco about the missionaries, and the large amount of good they had accomplished among the peoples of the Andes. Years ago only the Roman Church were tolerated, but now missionaries of every sect are made welcome, some coming from lands as far distant as Canada and New Zealand. Francisco thought this was only just and right.

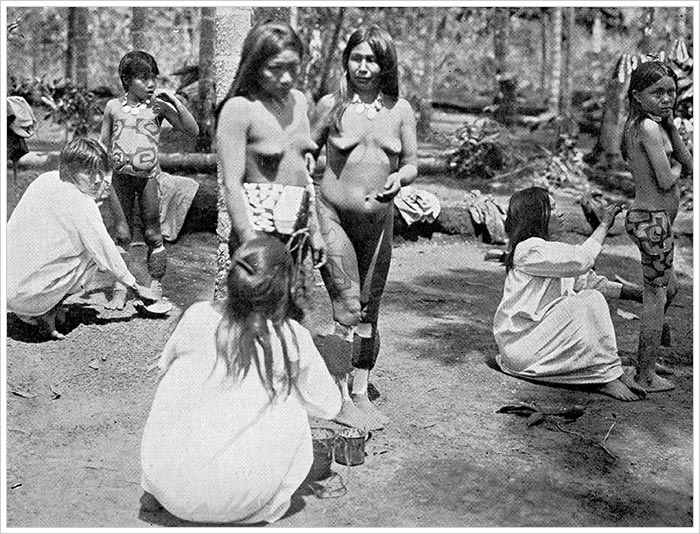

There are now many missionaries located in South America who visit all the Indian tribes, including the Cunchos of the Savannah of the Andes and the so-called savages of the campos of Central Peru. All are made welcome. The Indians all worship one god, and look upon the priests as the representatives of God on earth. They call their Church the Church of Christ.

The missionaries work amicably together for the common good. But I think they would obtain even better results if they did not crowd so much together in the big towns. I should like to hear of them visiting the out-of-the-way places more frequently. I have been where the Indians have been crying out for a priest or missionary and haven’t seen one for years. The little village in the Challana country may be mentioned as an instance, and I know of many others. In this connection I call to mind the opinion of two prominent missionaries—a Presbyterian from New Zealand, and another from Canada. They confirmed what Francisco told me, and said the head missionaries only cared to go to such places as had a big church and plenty of priests. One of these big pots looked like getting into trouble, for his people at Head Quarters wrote to him saying, “You have been in Bolivia five years; now come home and give an account of your stewardship.”

This man had been in Cochabamba all that time and had never been far from it, or absent for more than about two days at a stretch. He came to me and asked my advice. I suggested he should write saying he could not very well return home just then, as he was busy helping translate the Scriptures into the Quichua tongue. This was no lie, but he could have been easily spared, for there were then located in that far-away town no fewer than nine missionaries besides those of the Roman Church. As a matter of fact, one would have sufficed.

I am much interested in missionary enterprise, and am filled with admiration of the wonderful work some of the missionaries have accomplished in various parts of the world; but I cannot shut my eyes to the fact that in South America, at least, the Gospel message seems to have had a disastrous effect on the morals of the Indians. This may, of course, be attributable to the fact that the trader with the rum bottle follows hot-foot after the Gospel messenger. Until the tenets of Christianity were preached to them, immorality was practically unknown among the Indians. Writing of these people a hundred years ago, a well-known authority said, “Chastity, especially in the married state, is a national virtue.” As a Christian I cannot but feel humiliated when I think of the change that came over some of the tribes after they had heard the Word and received it gladly.