From Tipuani to Paroma, Part 3

That evening, while Mac and I were smoking after dinner, an old Indian came to tell us that near his sugar-cane field, some six leagues down the river, a big man-eating tiger, as he called it, had tried to attack his sixteen-year-old boy, and had also killed a small mule belonging to a rubber picker. As a matter of fact, these animals are of the jaguar species, only much larger. It seemed his boy was cutting sugar cane, and before going home went into the bush near the banks of the river, to get guavas, when he suddenly came across the animal eating a mule he had just killed; the beast, on seeing the boy, growled, and the boy jumped into the river just as the animal made his spring. Fortunately, he did not follow him into the water, although it is well known that these beasts swim well, and Indians have told me they have seen them in the water crossing over.

Mackenzie could not join in the hunt, as he had only just got over a bout of fever, and Perez, too, was down with fever; so it was decided that the Indian should take me next day to the dead mule, where I would sit up for the night on the chance of the jaguar or tiger returning to his prey.

The Indian, Miguel and I started off next morning after breakfast at 7 a.m., and crossed the river by the wire cable. We took a cooking pot, a kettle and provisions for three days, including a bottle of rum. The first part of the journey was by a path through the forest, close to the river. Some six miles from the village we saw some beautiful birds sitting on a big wild cotton tree, of a kind I had never seen before. They were about the size of doves, light green in body, with purple wings, scarlet breasts, yellow heads and black beaks, but they were not of the parrot species. This was the only spot in the forest where I noticed these pretty birds, and I saw them at the same place coming back. The path here took a turn to the right for about a league, amongst beautiful flowers and creepers, and some very large trees, of which several were rubber trees. It was fairly easy going, but we had to use the cutlass every now and then, and it was up and down hill all the time, though not nearly so steep as what we had been used to. Soon the path turned to the left again, and led down to the River Tipuani, just opposite the Texas Gold Mining Company; there was a small settlement here, where two Indian families lived; one of the men was away picking rubber for Perez, the other was working with the women and children in their sugar and maize plantation.

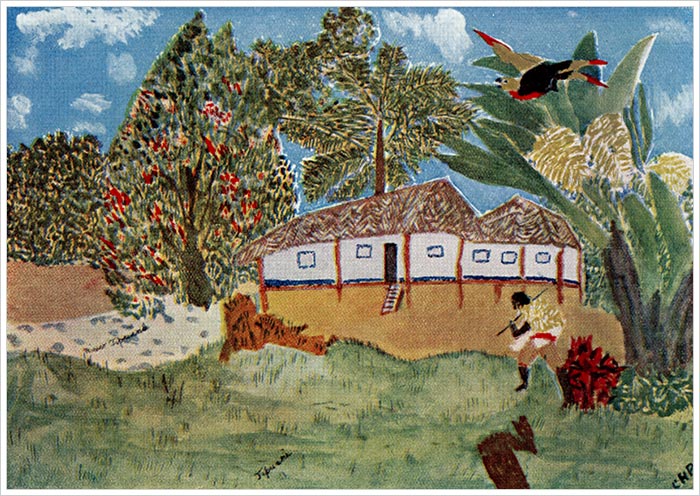

Gold firm headquarters on the Tipuani. Illustration from Adventures in Bolivia.

We rested here for a little, and made some tea, while one of the boys went across in his father’s balsa to Charest, the Manager of the Texas Gold Company, with a message from me, asking him to come along and join the jaguar hunt, but he sent back word that he could not come as he had a touch of fever just then.

From here we followed down the banks of the Tipuani for a mile to a spot where the river took a bend to the left, and another small stream came down from the hills on the right and joined it. This spot was, to my mind, one of the prettiest I had come across. On the left was the powerful and swiftly flowing Tipuani, on the right the stream, and all around was the forest, and the high hills crowned with patches of green grass with valleys between them. There were high palms everywhere, and big green heart trees in flower, which stood out prominently against the dark green of the forest. Beautiful flowers and creepers were growing on the banks of the rivers, and gorgeous blue butterflies, seven or eight inches from tip to tip, and green and yellow, and green and blue parrots were continually flying from one side of the river to the other. Overhead the sky was a clear blue; here and there were a few big vultures, flying high up, and waiting to swoop down on some dead animal which they would pick clean to the bones. I thought to myself how strange it was that this beautiful spot should be a haunt of malaria, where only the forest Indians could live without constant attacks of deadly fever. I took some views here with the kodak I carried.

Up the stream to the right was the place where the man-eating tiger had killed the mule. On the way we stopped for a few minutes at the home of my Indian guide, and saw the sugar plantation where his son was engaged cutting cane. This man owned a few head of cattle, which he had driven originally from the forest; there are a good many wild cattle to be found in the forest, though not nearly so many down here as in other parts. About two miles from his place we came to the dead mule, and found that the loins and part of one flank had been eaten away, and the throat torn open. I asked the man whether the animal had been poisoned, and he told me “not yet.” Jaguars and pumas always seem to find out if a beast is poisoned and, if so, often leave it and kill a fresh beast; I have seen this happen more than once. Nevertheless, these beasts have very often been poisoned, and I think what happens is this. If a horse, mule or a bullock has been killed, and the jaguar or puma, when returning to his prey, sees other animals near, he will kill a fresh one for the sake of the warm blood, which he will suck from the gullet of the newly-killed beast, but if the others have been driven away then he will go for the original kill. The dead mule had been dragged just inside the bush from a small green spot where it had been killed. The water in the stream here was about four feet deep, and the stream about fifteen yards wide. Miguel and I crossed over to the other bank six feet above the stream at the foot of the forest, where I decided to wait for the jaguar. It was then 5.30 p.m., and the Indian returned to his home, promising to bring back fresh milk and eggs for us in the morning. After a good dinner of challona stew, we sat down to await developments; I had my big Winchester rifle and the magazine was full. The night was fine, the moon almost at full, and fireflies everywhere. Nothing happened until 9 p.m., when a big tapir walked slowly across the green into the forest on the other side. A little later there was a distant peal of thunder, a sign that a storm was coming, and a cloud passed over the moon for a few minutes, but it was soon clear again. I looked at my watch, and it was a few minutes before ten. A minute or two after, we heard a movement in the bush opposite, and a long animal the size of a small donkey walked out on to the green patch in front. He noticed us at once, stood still broadside on, and turned his head and looked at us. It was the man-eater and mule-killer, and a splendid chance to get him. The moon was clear of clouds, and he could be seen quite distinctly. I took steady aim, with the muzzle pointing dead behind the shoulder, and pulled the trigger, only to find that the cartridge missed fire. I quickly slipped it out again, and pushed in another, but the same thing happened. In went a third, to no purpose, and then without turning round I said to Miguel, who was a few feet behind me, “Something has gone wrong with my rifle; if he comes across to us, you take the cutlass, and I will take the axe, and we will club him if we can while he climbs up the bank.” Fortunately, he never came, but after looking at us for a minute or two he turned round quietly and went back into the forest, and we saw no more of him that night.

The misfiring of the rifle was most unfortunate, but entirely my own fault, as I discovered a few days later. I had kept it well cleaned and oiled, both inside and out, but had forgotten to fire a trial shot before leaving Mackenzie’s place, and on taking the trigger off I found a small bit of gravel grit jamming it, with the result that, although the trigger worked well enough, it failed to touch the cap. As soon as I put it on again, it fired as usual, and here was I abusing the cartridges, when it was my fault all the time for not trying a shot first. It just shows that you can’t be too careful.