From Tipuani to Paroma, Part 8

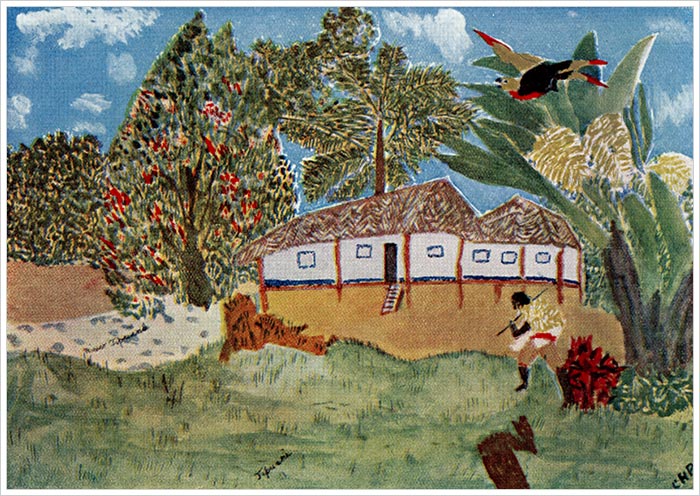

After breakfast the men came over with a big five-pole balsa, and took me across. They told me that the river at this crossing was seventeen feet deep in parts. There were several settlements on the bank, inhabited by Indians; Thomas Cortez’s place consisted of five sheds made of poles and roofed with palm branches and wild banana leaves. He gave me a good big one with a bamboo bed almost three feet high and three feet broad and seven feet long. There were some fowls, turkeys and pigs and two cows tied up close by. I told Cortez that I was not tired, and could easily continue the journey, but he replied that we could not proceed for ten days, as those were his orders. He had been told to look well after me, and every day his wife brought me good food, eggs, milk and coffee in the morning, stewed fowl and rice and fruit and bread at 1 p.m., and a good meal again at night. She also washed my clothes. They had guns and rifles there, and shot a good deal of game, especially poujil (pronounced pooheel), which are birds about the size of a big fowl, and very good to eat; they shoot them as they are roosting on the trees. They never fire unless they are quite close to the bird, as powder and shot are too scarce in this out-of-the-way place to be wasted on fancy shots. All the natives here sleep either on the floor or on a bamboo bed, and very few of them have hammocks, unlike the natives of Guiana and Venezuela, where every one carried his bed, a light net made from fibre or strong cotton, which is hung up between poles on branches of trees. While I was here, I shot a big swamp deer on the run, as he was crossing one of the narrow Indian trails; to the great satisfaction of Cortez, who said that the meat would be good roasted. Every night Cortez slept in my hut, at the further end, and there was always a man on sentry duty all night. When I went for my bath each morning at 6 a.m., two armed men always stood a little distance off, though the stream I bathed in was only a few yards from my hut, as I used to go down in my nightshirt and dress by the river. After breakfast I generally took a net and went down to the banks of the Challana to catch butterflies. I was always escorted by two armed men with rifles, who followed a short distance behind. They took every precaution never to let me out of their sight; later on Villarde told me the reason why. Cortez told me that they had a great quantity of rubber for sale both here and at Paroma, and that the price was regulated by the Cacique at Paroma, nobody being allowed to sell for more than one hundred bolivians a quintal; this worked out at 1/10 per lb., and the market price in La Paz was then 4/6. Out of every 100 bols, ten bols was paid to the Cacique, and all rubber collected by the Indians in this district and Paroma paid ten bols per 100lbs. to Villarde as well. On the Tongo side where Villavicencia, Villarde’s brother-in-law, was in charge, the same payment was made. Villarde was a rich man, for out of his share he kept half, the balance going to his various lieutenants in the different districts. Each district paid separately, so that some were better off than others. By this system the pickers got 80 bols clear per 100lbs. (£7 6s. 8d.).

No trader was allowed to pay more than 100 bols per quintal, nor to charge more for his goods than they would fetch at the biggest and most important stores in La Paz. The year before last a trader from La Paz had come down to the river with twenty little mules loaded up with goods to exchange for rubber, and paid the Indians in goods and money at the rate of 105 bols instead of 100. He thought himself very smart, but it soon got to the ears of Villarde, who told the Cacique. It was decided when this man, Hernandez, returned, to confiscate the whole of his stock and all his mules, and to order him never to return to the Republic of Challana again. Last year Hernandez turned up with thirty-five mules and goods; the Cacique’s orders were carried out, and all his mules and goods were taken to Paroma. Cortez said the reason this order was made was that if the natives were given permission by the Chief to make their own prices they would get out of hand. There were watchmen always guarding the river at every available ford, and it was quite impossible to cross except in balsas, which were never left on the Tipuani side. Cortez told me that you could travel by balsa down the river without any difficulty to Port San Antonio, that this river joined another big river, probably the Gy Parana, which in turn joined the Madero and then the Amazon; the River Beni flows into the Mamore, then into the Amazon. My opinion is that the Tipuani and Challana have their source from the stream just above Tiquiripaga, but of course I am not sure, as I have never myself tried to trace the source of any of these large tropical rivers.

The scenery about here was very grand. The river ran between two high cliffs of red sandstone and red clayish soil. Large trees came right down to the water’s edge in some places, and in other places the banks were perpendicular precipices of deep red coloured soil and rock without any trees. All round was dense forest land, except at the Anhuaqui Settlement, where there was a wide stretch of prairie reaching to the foot of a very steep and densely wooded high hill with a red path leading up to the top. This hill was some nine miles from here, and Cortez pointed out this particular path to me as our way to Paroma. It did not look at all pleasant to have to walk up there, but it had got to be done the next week.