A Journey Into the Interior, Part 1

I left Mollendo by the eight-thirty train on Wednesday morning, and arrived at Arequipa at six-thirty the same night. Next day I happened to meet my friend, the consul for Uruguay and Peru. It appeared that he also was interested in the Province of Inquisivi, and intended to take the Peru and Bolivia train, leaving Friday morning at eight for Puno, the terminus, situate on the banks of Lake Titicaca. So we agreed to travel together. A description of Titicaca was given in my Adventures in Bolivia, hence I need only add that one of the islands near the peninsula of Capacabana is held specially sacred by the natives. For, according to their most highly respected traditions, it was here that Manco Capac and his consort founded their glorious empire. Here may be seen the ruins of an old monastery, which was in existence when the Incas came and conquered the Huancas. There are stones in this great building, weighing twenty tons at least. Alongside the principal doorway, there is one still standing that I should put at twelve tons. Five hundred priests, I believe, are attached to this monastery.

At Puno I met a Russian Count and his wife, who were accompanied by a Baron von K——, who acted as secretary to the Count. They had been exploring the sacred isle, and intended to extend their trip as far as the great gold river, Tipuani. Unfortunately—so I heard later—the way up the Sorata Pass proved too much for the Countess and the Baron. So the whole party had to return to Puno. The Count stood it better than the others, and naturally so, for he was a big fellow.

Crossing the High Andes by the Pass of Sorata is no joke for a woman; in fact old Naboa told me that in all the sixty years he had been acquainted with that district, he had heard of but one lady who had accomplished the feat. She was a Countess—Countess M. I’ll call her—who had run away from her husband with a Baron R. The Count, it appears, followed them with his revolver, intending to shoot the guilty pair when he came up with them. The runaways put in six months at Tipuani. Baron R. occupied himself prospecting for gold, three miles from the village. He engaged six natives and four West Indians to dig and wash for him. One day a West Indian told him a Gringo Caballero, i.e. a foreign gentleman, lay very sick of fever at Gritado, a place ten miles the La Paz side of the river. Baron R. took pity on the sick man, and started off at once in search of him, accompanied by the Countess and six Indians with a stretcher. It was intended to fetch him home to their place and nurse him back to health. They found him, lying on a mattress, in a hut belonging to a man called Ricardo Rodriguez. Picture their surprise when he turned out to be no less a person than Count M. himself! The situation was most embarrassing; but Baron R. and the Countess made the best they could of it, and gave the sick man every attention; so that, within a little while, he became convalescent, and fit to be removed to their place. There they nursed him back to health; explanations were given and received, and, ultimately, all three became reconciled and left Tipuani together, apparently on the best of terms with each other.

We travelled from Puno by the lake steamer to Quaqui, and then took train to La Paz Alto. Thence we journeyed by coach as far as La Paz. Following my usual custom, I put up at the Hotel Guibert, and persuaded the consul to do the same. The proprietor was absent in Europe, but I was glad to hear the Jura baths had quite rid him of his rheumatism. In return for my advice about taking the Jura cure, he made me free of his house—a very pleasant and delicate way of expressing his gratitude.

We stayed here five days, while the consul’s buggy horses rested. They had come up from his mine near Incasiva. I occupied myself in getting five cargo mules, and two for saddle-work. The latter were beautiful creatures, and cost, in English money, £30 apiece, or half as much again as the cargo mules. I named them Batson and Charlie, after two mules that took my fancy in a Barbadian tram-car. Batson was black all over; Charlie, chestnut, with dark chestnut mane and tail, and a black mark right down his back. I loaded up the cargo mules with provisions—not forgetting to include some old Madeira, half a case of whisky, six bottles of old port, and several pots of Liebig’s extract—and sent them on ahead to Sicasica, ninety miles away. I followed three days later, by the diligence that runs twice a week between La Paz and Oruro. The driver was an Indian, famed for being extremely punctual. On one occasion, it is said, he refused to wait more than five minutes for his boss, who had arranged to travel with him. The laggard, as mail contractor and so forth, was a pretty big bug in his way. I occupied the box-seat on the trip referred to. I was on my way to Oruro—the racing season in Chile having concluded—to call on my friend and patron, Mariano Penny, previous to my starting on an experimental trip over the Andes, in search of some old mines that had been worked by the Ancients, and lost to sight for many years. Well, we started without the boss, and in due course arrived at a place about ten miles from La Paz Alto. Here we stopped fifteen minutes to change mules. Before this operation was completed who should appear upon the scene but the missing man! He had driven a four-horse buggy at a furious pace all the way from our starting-point. Much to my relief, he did not rave at the driver, but, on the contrary, made him a present of five dollars for sticking to his time schedule.

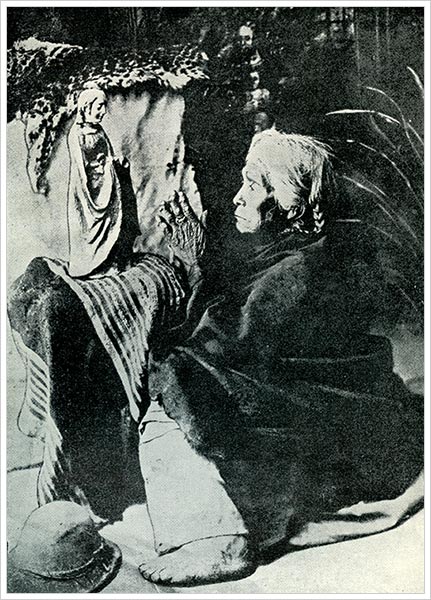

I travelled so often with this Indian that we became quite good friends. He sometimes handed over the ribbons to me, while he chucked stones at the mules to induce them to show their best paces. Full lick we would go over the Camp, taking boulders, ruts, and holes in our stride. There was no road, properly speaking, but only a track beaten down by the traffic. We often passed llamas loaded with corn and attended by Indians, who looked very picturesque in their different coloured ponchos and caps made of llama or vicuna wool. The Indians never start their llamas on a journey before 9.30 a.m. They march on till 3.30 in the afternoon, resting for rather less than an hour midday. Ordinarily a llama should cover twelve miles a day, and carry from 35 to 50 lb. Some of the biggest can manage 75 lb. These are highly valued by their owners. On short journeys, when employed to convey gold, silver, tin or copper ore down from the mines, a llama is often burdened with 100 lb.