The Second Attempt, Part 1

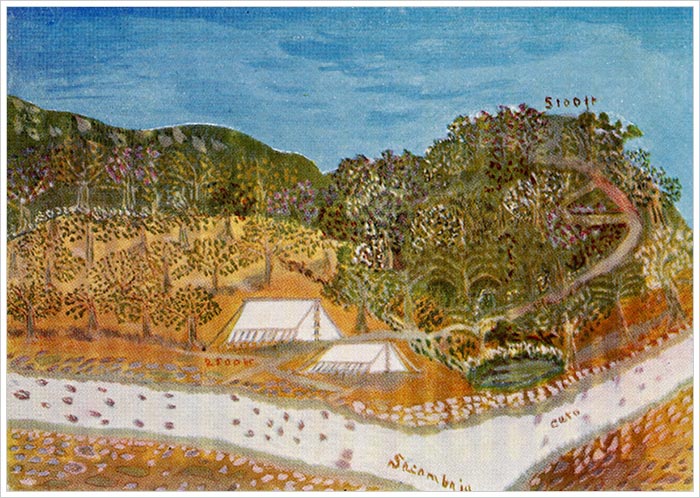

In March of the next year I started off again for the hills to renew the search. I got to Oruro at the end of the month, bought four mules for cargo and a saddle mule for myself from an Argentine trader, and went on to Sacambaja via Cochabamba and Palca. At Cuti I stayed for five days with my old friend Mendizabal, who came on with me to the hill. The first two days were spent in going for wild cattle, as Mendizabal wanted to make some charque for his own use, and I wanted some for my camp; we got four cattle, and divided up the meat.

On the third day I started uncovering the top of the hill, working downwards in a “V” shape from where I had left off. Exactly fifteen feet down I came to a solid mason work, one big square stone; and then a slab of slate stone; this formation went on for twelve feet down. Then I came on a stone cobble path, which I concluded was the bottom of the cave, but there was no sign of any door, so I decided to drill a hole between two blocks of stones. I consulted Mendizabal, and he thought with me that this was the work of man, and not a natural formation. He brought his son and five Indians to lend a hand. Before we started to drill, one old man said we ought to offer up a gift of a cock, some wine and bread, and leave it there for the night. Mendizabal said we must humour these people. So the offer asked for was duly left. In the morning the things had gone! They had probably taken them themselves but swore they had not done so. We pretended to believe them.

We drilled a hole for three feet and a half, and then pushed a thin bamboo twelve feet long through; it appeared to touch nothing except in one corner where it seemed to prod something soft.

Suddenly a very powerful smell began, so strong that it made us all feel bad; it smelt like oxide of metal of some sort. Mendizabal and his son both went home feeling bad, but he got over it in two days, his son felt unwell for a week, but I got over it in a few hours. Three of my men left feeling bad and never returned. The other three men I had went up with me again two days after, and when we were near the top we saw over a dozen big condors, hovering about quite close to the works. Zambrana and Manuel both told me that the three Indians said this was a sign there was something buried inside; they all seemed rather funky, so I said I would give it a rest for a fortnight to let it get well ventilated, bearing in mind what the paper said about there being enough poison inside to kill a regiment. This was on June 3rd, 1906.

On the night of June 4th, the weather completely changed, and at 8 p.m. the thermometer stood at four degrees below zero. In the morning at 7 a.m. it was seven degrees below zero, but at 9 a.m. it began to get warm again, and at 12.30 it was eighty-seven above zero, going down again after sunset quite suddenly. At 8 p.m. that evening it was fourteen degrees below, next day between 12 to 1 p.m. eighty-six degrees above. This was a phenomenal year; there was a black frost every night, and a lovely blue sky all day. On the sixth night after the change had begun, the thermometer actually went to twenty-seven degrees below zero, and in the morning was twenty-eight degrees below. Zambrana said he could not stand the cold nights even with good food, a tot of rum and a good fire, and would have to go home; he promised to return in a month. The three Indians also said they had had enough, and left the camp two days after Zam, also promising to return. I had already sent Manuel to Barber’s at Cochabamba for some provisions, so I was now left quite alone. I made it a point never to let the two fires go out. One night, at about 10.30, I had turned in with a big log fire burning outside my tent door, when I heard a rifle shot, then another and yet another, as though some one was firing a rifle, and the bullets were whistling over my tent. I got out of bed and lay under the bed with my good double-barrel rifle loaded and my colts as well. I counted seven shots, and then came to the conclusion that it was somebody trying to scare me, but with no intention of shooting me. So I got back to bed and shouted out, “Who is there?” Two more shots came in quick succession, and then they ceased. The next morning nothing was to be seen. That night the same performance took place from eight to ten, but this time I did not bother, being convinced it was a case of trying to scare me to leave. This was four days after my men had gone.

After this, I heard nothing further and never found out who fired the shots. Two days afterwards I was very pleased to see four likely looking Indians with their packs come into the camp asking to be taken on. I took them on gladly at 1/- a day, and their food, which was the price they asked. Next day I left one in the camp to attend to the kitchen, and took the other three with me. I decided not to disturb the stones any more, but to go working away to the left, leaving the stone path as a starting point.

The weather continued the same and was even colder at nights, and in the early morning, with tropical sunshine all day. I kept in good health and enjoyed it although it was rather too cold at nights.