The Caballo Cunco Treasure: First Attempt, Part 2

After a stay of two weeks, I started for Cochabamba, riding the horse on the first day, and next day a good little white mule. The journey of 190 miles took eight days’ easy travelling. We started each morning at 9 a.m., and camped every afternoon at 3 p.m., renting an Indian hut for the night. Each evening, after buying fodder for the animals, eggs and mutton, and whatever else was wanted, I generally took the gun for an hour or two, and shot some doves and other birds, which we ate cold for lunch next day.

The first day’s journey was over the high flats, a sandy desert, with little feed for the animals. Indians with llamas, each carrying a small load, passed us frequently on their way to Oruro, and now and then we met long strings of mules, led by their bell mare. The bell mare carries nothing; her job is to lead the mules, and they follow her in single file, stopping only when the bell stops.

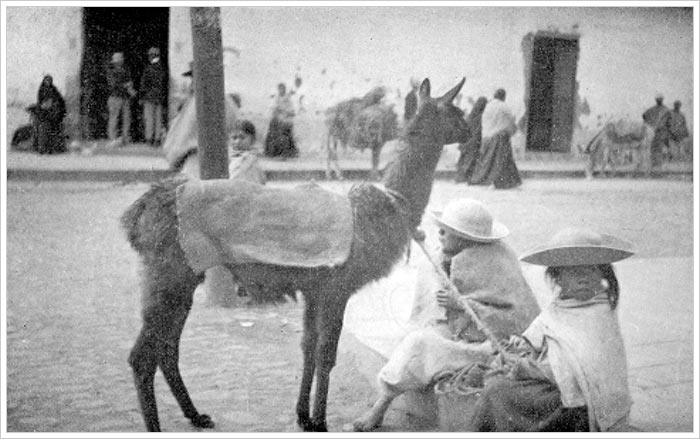

Llamas outside the town of Caxamalca. Illustration from Adventures in Bolivia.

The rest of the way was through a more fertile district, which bred sheep, llamas, cattle, donkeys, mules, and even a few horses. I saw Indians ploughing the fields with the same wooden ploughs as were used hundreds of years ago. Occasionally we passed small wooden carts drawn by oxen, with heavy wooden wheels made of one piece.

The crops in these parts are barley, wheat, potatoes and, further on near Cochabamba, maize, ochres and yucas. Fresh mutton can be bought, the usual price being about 4/- to 5/- a sheep; also home-made bread, fowls, eggs, and guinea pigs, ochres, chuno, potatoes, onions, barley in the straw, green barley and alfalfa. The native drink of chicha, made from corn, can also be bought quite cheap every few miles.

The weather was fine the whole time, warm in the day-time, and cool at nights, and the journey was a much more enjoyable one than going down by diligence. There were several rivers to be crossed on the way; between November and April, they are difficult to get over, and people don’t travel much from Oruro to Cochabamba during those months.

Cochabamba stands 8,200ft. high, with a climate which is one of the best in the world; it is never too hot in the day, and cool at night. Rents and living are very cheap. The market master regulates the prices of all meats, beef, mutton and pork. Vegetables are plentiful, and fruit of all kinds may be purchased on the market. There are no hotels to speak of, and no street cars or cabs for hire. The streets are all well paved with stone with a gutter down the centre. All the houses have heavy iron bars to the windows, and big, solid bolts to the doors as well. Murders are not uncommon, and the criminal is seldom caught, which is due not so much to the negligence of the police as to the number of hiding-places where the criminal can easily conceal himself for a time. When a murderer is caught he is made to undergo a public trial in the square of the Court House, and if he is found guilty he is taken to the spot where the crime was committed and shot there. I saw one such trial in Cochabamba. A bad Cholo had asked and received the hospitality of a man and his wife for the night, and while they were asleep had killed them with an axe, and stolen a sum of money he knew was in the house. His bloodstained clothes convicted him, and he was shot. I was told by a man who knew that this was the first occasion for a long time that a murderer had been caught. The cathedral, which is built of stone, faces the big square and garden; the Hall of Justice, military barracks, and police station are on the opposite side. Six hundred priests live in the town. Chiquitos, where the Jesuits found a lot of gold, is twenty days’ journey by mule, and the famous Espirito Santo gold mine worked by them is ten days by mule. There is bear shooting three days away. I rented a nice little house on the outskirts of the town near the river, with large garden and open air concrete bath. Only a very few houses contain proper lavatory accommodation; otherwise they are very well built and quite comfortable. I made this house my headquarters for three years, while prospecting for old mines and looking for the Jesuit treasure. In front of my place were the Municipality grown alfalfa fields for the Government animals; they were guarded day and night by two armed watchmen, to prevent them being cut by thieves. It costs little to keep animals here; barley and alfalfa can be bought by the load, one mule cargo for about 4/-, and two cargoes, one barley and one alfalfa, served for my horse and four mules a day.

Opposite Cochabamba, on the other side of the river, a German Company had a large brewery, and made very good beer; a dozen large bottles cost 2/-, and the bottles cost as much as the beer. Imported Bass beer cost 2/- for one big bottle, a bottle of good whisky 10/- or 12/-, and Three Star brandy 16/-.

After a considerable amount of trouble, I located Zambrana, who lived a day’s ride from Cochabamba. He had not seen old Jose Maria for many years, and the priest, Father San Roman, who used to pay him, had died, but he said he knew Jose Maria lived near a place called Cuti, which was thirty-five miles from Palca. Zam, as I always called him, had never been to either of these places, but knew the way as far as a mountain village sixty miles from Palca. He agreed to join my expedition as campman and butcher, get water and wood, and help the cook, so I took him on; he was to find his own mule.

I had two tents made here, one for myself 16ft. by 12ft. and 9ft. high, and the other was 10ft. by 10ft. and 9ft. high; also a strong folding-up canvas catre 3 and a half ft. broad and 7ft. long, which, with a horse-hair mattress, made a most comfortable bed. I also got together provisions for four months: sugar, rice, biscuits, jams, tea, cocoa, coffee, and some tinned meats, salt, ship’s biscuits and other things. Zambrana told me that round about the department of Palca both sheep and flour were plentiful and cheap. The Indian wife of Manuel, the mule man, made splendid bread, and at the different stopping places we often borrowed the use of a bake-oven, and stayed a couple of days to make bread. It is well worth the extra trouble to get good, wholesome bread made with flour that retains all the good ingredients of the wheat, which is always possible if it is crushed by the stone mill process. I also took two dozen bottles of rum, one dozen of the best for myself, and a dozen of a stronger, but inferior, quality for the men. With the exception of the things I brought out with me, such as Liebig’s Extract, a thing I never travel without, everything was bought from Barber & Co., who traded goods for rubber up the Beni, by advancing money and goods to traders for rubber to be delivered in two years’ time. Alfred Barber was the manager for this firm in Bolivia; in London and Hamburg the firm was Brandt & Co. Of course all the traders who dealt with the firm on the two years’ credit system had to show substantial guarantees in the form of unmortgaged property, otherwise such firms would soon come to grief. Barber himself had to put up a guarantee of several thousands of pounds (a legacy left him by his godmother) to be made managing partner in Bolivia.